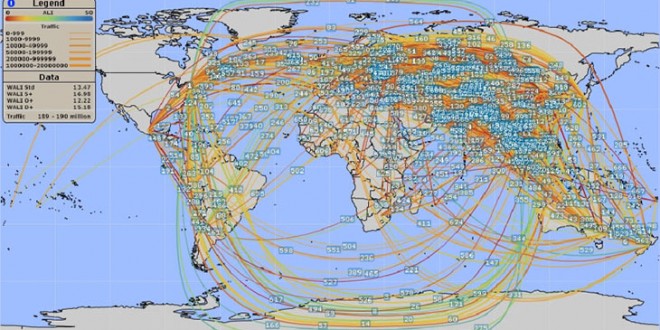

The Jet-Etihad deal last year brought to the forefront the issue of bi-lateral air services agreements or bi-laterals in short. Bi-lateral agreements and their impact on the aviation sector including routes and profitability is extremely critical. We present a two part series that highlights bilateral agreements and freedoms of the air.

In part one, we will cover what are bi-lateral air services agreements and how they function.

What are bi-lateral air services agreements and how they function

Air services bi-laterals have been inextricably linked with the aviation industry. The effects of air services bi-laterals are not limited to airlines. They affect airports, and other stakeholders in the value chain such as ground handling firms, fuel providers, maintenance providers, etc., the local economies are also impacted due to employment and fees generated, air freight, and by extension the country as a whole.

An air services bi-lateral is a treaty between two nations which governs the commercial air transport and carriage of passengers and goods between the two nations. Most bi-laterals have evolved after World War II when 54 nations came together, in Chicago to discuss civil aviation, and agreed on a series of rules in the Convention on International Civil Aviation (commonly known as the Chicago convention). These then came to define the overarching air transport policy framework under which air services operate across the globe. The Chicago convention also established the International Civil Aviation Organization better known as ICAO (pronounced “eye-kay-oh”), the United Nations organisation responsible for international air transport globally.

One of the first air services agreements was between the United States and the United Kingdom. Known as the Bermuda agreement it was signed in 1946. The agreement defined trans-Atlantic routes and which airports and seaports (for the flying boat services) they could be flown out of; intermediate stops; and finally procedures for tariff determination and regulation. Most bi-laterals till the present day have evolved from the Bermuda agreement.

Bi-lateral air services agreements, in general, have provisions on:

- Traffic rights: routes that can be flown, cities that can be served and any associated freedoms of the air which are flying rights and restrictions agreed upon between countries

- Capacity: the number of flights that can be operated or number of passengers that can be carried between the bilateral partners.

- Designation, Ownership and Control restrictions: ownership and control criteria airlines have to follow to avail of the bi-laterals

- Tariffs: in some cases tariffs have to be submitted to a regulatory body

- Other provisions: addressing issues of competition, labour and employment

The rationale behind bi-laterals has been two-fold. Historically, most of the airlines were state owned and thus there was a need to ensure that the home carrier flourished. In addition, due to the labour intensive nature of airlines and the economic multipliers air services provided (in the range of 3X to 7X), protectionist elements were included with a view of aiding the respective countries’ economy and local employment.

India and its bi-lateral agreements

India has approximately 100 bilateral agreements. Our oldest bi-laterals were with the UK and South East Asian nations of Thailand, Hong Kong, Singapore and Japan. As of date, India’s most liberal bi-lateral agreement is with the U.S. where Indian carriers are afforded the right to have “any number of services with full traffic rights from/to any intermediate/beyond point.” This excludes domestic U.S. routes.

Our most restrictive bi-lateral is with Hungary and Lesotho which restricts airline services to a mere one flight per week between the two countries. Viewed in terms of the traffic potential between the two nations, the bi-lateral is sufficient for any airline wishing to start services.

In terms of capacity entitlements, which is defined in either number of flights (services) per week or in number of seats, Sri Lanka has been afforded 112 services per week followed by, Saudi Arabia at 75, Germany at 74, Bangladesh at 61, and the United Kingdom at 566 services per week.

The United Arab Emirates (UAE) which comprises of seven states (each known as an Emirate) is a special case as bi-lateral agreements have been negotiated with four of the Emirates rather than with the UAE as a single country. Sharjah has an entitlement of 18,816 seats per week; Dubai of 54,200 seats per week + two percent; Abu Dhabi 53,000 seats per week, up a massive 300% from the earlier 13,300 per week; and Ras al-Khaimah which has an entitlement of seven services per week. These generous allocations are one of the many factors that have allowed gulf carriers like Emirates and Etihad to grow significantly. Today India contributes over 12% of Emirates airline’s total traffic.

In comparison, bi-laterals with other nations that have also developed large transit hubs are more restrictive. For instance, Singapore is allowed only 28,600 seats per week; Qatar 24,292 seats per week; Thailand 23,609 seats per week and Malaysia 22,531 seats per week.

Outlook

Bi-lateral flying rights and capacity entitlements are strategic assets for airlines and for the country. The argument against generous bilateral agreements with Emirates like Dubai and Abu Dhabi is that that they have developed hubs with far better connectivity and several sources of competitive advantage thereby effectively resulting in leakage of traffic (defined as traffic that is originating in India but connected to a final destination via a hub outside of India). This effectively limits the ability Indian airports and airlines to grow and compete effectively, consequently impacting the entire aviation value chain and the local and national economy.

As India’s middle class continues to grow, an increasing number of travellers will take to air travel. Forecasts indicate that India could have in excess of 414 million total passengers by 2020. With the potential to become one of the largest air travel markets worldwide, bi-laterals in the coming years will become even more important to India and the countries and airlines looking to access the growing traveller base.

*note: numbers on capacity entitlements have been averaged out. May vary from actuals.

Stay tuned for part two of this series which will be published next week and will cover Freedoms of the Air and its impact on the aviation industry.

Bangalore Aviation News, Reviews, Analysis and opinions of Indian Aviation

Bangalore Aviation News, Reviews, Analysis and opinions of Indian Aviation